Auntie Do goes to Bucharest (1924)

|

Passport photo of Aunt Do Hahn, May 1924 | . |

In the living room, Grandpa Aarsse reads the newspaper, Grandma Hahn writes letters, Aunt Jettie makes Dutch for school; one stove for the whole family. Then Grandpa says: “Say Do, isn’t this for you? Baroness van Nagell is looking for a teacher for her seven-year-old daughter by advertisement. The family lives in Bucharest” . “Yes,” says Aunty Do: “I’d like that”. Whereupon Granny takes a clean sheet of stationery and starts writing. Now what do you put at the top of such a letter? Aunt Jettie looks it up in her Dutch book, and Oma writes: “Hoogedelwelgeboren Vrouwe”. Then each in turn says one sentence.

Aunt Do fulfilled all wishes: she could sing and play the piano, spoke French, German and English (the latter not that fluent, but well). Now for a reference. At least the head of the school. Aunty Do taught as a pupil with acte, which meant she did not do much other than check schoolwork and give a (nasty) lesson in the headmaster’s class twice a week. It was a backstreet school and she quite wanted to leave there. Who was the poshest family member to list as a reference? Uncle Charles was a legal secretary, Uncle Guus was a doctor. Finally, they decided to give the name of Mrs van Limburg Stirum, who did attend Uncle Guus; her husband was also a doctor.

Within a week there was a reply asking if Aunt Do wanted to visit the Queen’s Grand Mistress, Countess van Linden. She was then asked to stay for three days at De Schaffelaar home in Barneveld. Aunt Do understood that they wanted to see how she handled her fork and knife at dinner. Aunt Do was supposed to be “en famille”, which meant having lunch and dinner together with the family unless there was a big dinner. The family at the Schaffelaar consisted of: Grandpa, who had a great moustache that curled up in two curls; he was affectionately called “Kokoeris” by Grandmama. Then Grandmama, who wore a gown that had been out of fashion for about 60 years, with a skirt with bumper straps down to the floor and a stand-up collar with boning. There was also an unmarried sister of Grandmother who wore roughly the same clothes but slightly lighter in colour. The young baron had been first secretary at the embassy in Berlin. Finally, seven-year-old Jeanette and a baby, Egbert Joost, who was looked after by a German Sauglingschwester. Aunt Do, apart from teaching Jeanette, would also take her to dancing lessons, go for walks with her, etc.

Jeanette spoke only German much to the annoyance of Grandmama and Grandpapa. Aunt Do had brought Rie Cramer books for her, sang songs for her at the piano and walked with her and Fräulein and the baby in the pram. Everything went well: Aunt Do had just spent three months in Lübeck and spoke fluent German and the child liked her. On the last day, Aunt Do was alone at breakfast when Grandmama talked her through it. Grandmama said she found it difficult to let Aunt Do, who was still so young, go with her to Bucharest with the young lady, who Grandmama said was stark raving mad. We are waiting the moment or to put her in an institution said Grandmother. But since Aunt Do did want something other than school, she decided to go anyway despite Grandmother’s warnings.

So she boarded the Orient Express in May 1924 and travelled for three days and three nights in a row. The family had a compartment for the Baron and Baroness, one for Aunt Do and the child, one for Fraulein and the baby and one for the Dutch houseboy who was called Stoutener and was a “hobo” (cf Aunt Do) and their numerous suitcases. Aunt Do slept in the top bunk and woke up the first night to crying. At first, she didn’t know where she was or where the crying was coming from. Then she remembered the child: she looked in the bottom bunk but the child was gone. Searching for it, until it turned out that the child had fallen between the seat and the banister; it couldn’t get out, despite pulling at arms and legs. Aunt Do then went and woke the parents from their sleep and with combined efforts they pulled the child out of the sofa.

The family first went on holiday in the mountains as all well-to-do people from Bucharest did. They went to the holiday resort of Sinaia, a spa in the Carpathian Alps. There was also the palace of Karna Silva (?). When they alighted in Sinaia with their mountains of suitcases, there was a goods train, loaded with sheepskins, between the platform and the station. That train did not leave, so the whole party had to climb over and through that sheepskin train with suitcases and all. At the station, the Buick of the Dutch Embassy in Bucharest was already in front, with the Dutch flag in front. In those days, all diplomats’ cars had priority in traffic, whether the light was red or not. When Aunt Do was alone in that car, she also drove through all the red traffic lights.

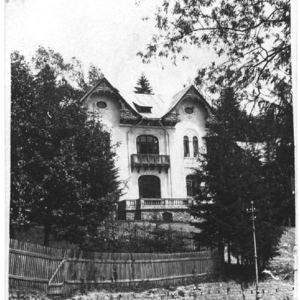

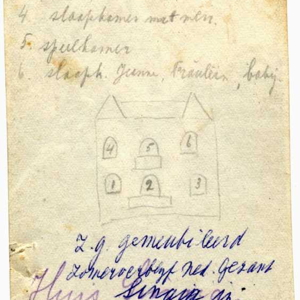

The family had rented a villa built against a hill. Down an unpaved road, three living rooms were joined together, with a terrace in front of the middle one. There was no furniture in these rooms: just a writing desk, a divan and a chair, nothing else, no curtains, no furniture. Behind the middle room was an open staircase leading upstairs. There were also three rooms there at the front (more at the back because the house was built against a hill). The middle of the three upstairs rooms was dining room, one room next to it was for the couple, the other for Fraulein and the two children. But where was Auntie Do supposed to sleep? At the back of the house was an outside staircase that led to the servants’ quarters. There, in one of the rooms, stood a white bedroom furniture which was then carried down to the three parlour rooms and that was where Aunt Do slept during the holidays: in three rooms without curtains. People regularly asked where the furniture was? Then came a few rattan chairs or a box with all sorts and sizes of net curtains, which were nailed to the windows.

Aunt Do started teaching reading and arithmetic in Dutch. In the afternoon, she walked with the child who stubbornly kept talking German. Until Aunt Do said: “There has been war with Germany here recently, so if we see a policeman we will deliberately start talking loud Dutch”. The result was that the child spoke Dutch in a fortnight; she could do it best but she refused.

Ms van Nagell now went to Bucharest to hire an embassy. The previous Envoy was a free-spirit and had lived in a hotel, hence.

|

|

The Nagell house |

|

Do Hahn teacher for Baron van Nagell April 1924- July 1925. Legation de Pays Bas, Boulevard Lascar Catargin 30, Bucarest. |

Ms van Nagell indeed was an anomaly: she did not trust anyone and always thought people were out to rob her. This necessarily led to scenes with the staff. Aunt Do was (at the time) so gullible that she did not understand what the baroness meant when she mentioned a roll of silk that had disappeared and thought she was joking. So she did not respond and thus escaped a lot of squabbling.

During the holiday period, the rainy season arrived. The villa became so damp that at Aunt Do’s room, mushrooms grew out of the walls. The servants lit the stoves, but that produced so much smoke that everyone had to go outside, causing the baroness to get bronchitis. She then decided not to eat in the dining room anymore, but halfway down the stairs. There was a small square plateau there where there was often sunshine. The dining table was set there and so the family ate halfway up the stairs while the house servant meandered along with the dishes. All completely official, with the baron in dinner jacket and the house servant in livery.

In September, the family finally went to Bucharest. The embassy was on a boulevard, on the outside of the city. Walking down the boulevard, you came to one of the chaussées that ran from the city centre outwards. On that chausséé was a large triumphal arch, but with a fence built around it. The figures on the drum arch had lost their heads and arms due to the poor quality of the casting.

Until Baroness van Nagell came, Mrs Dozy had been the first lady of the Dutch colony. She was now dethroned and the two women greatly annoyed each other.

Whenever Mrs Dozy came to tea, Aunt Do was also asked. For instance, Mrs Dozy would then say to Aunt Do: “You must come to tea with me sometime. I will send the car.” “Oh no,” spoke Mrs van Nagell then: “No way, she’s going with our car.” In Bucharest there was an association, the YWCA, of which many noble ladies were members. That association had a house where girls could stay and where you could also drink tea. Nobody came: the decent girls didn’t come there and the less decent girls didn’t like it there. Movrouw Dozy now thought that Aunt Do and Fraulein should surely drink tea there in that house. “No way,” cried Mrs van Nagell: “Aunt Do is here and is family”. But as soon as Mrs Dozy had left, or Aunt Do was taken to the YWCA. Once there, she had to tell all about marrying by proxy. That was so interesting, no one had ever heard about that before. By the way, Aunt Do was not just any teacher; she was, according to the Baroness: “a qualified teacher”.

There were a total of 13 servants (counting Aunt Do and Fraulein). Most were from Zevenbergen, which had formerly belonged to Hungary. The baroness had the best cook in Bucharest, whom many envied her. From that cook, Aunt Do received marriage proposals several times, conveyed by Fraulein when she had prepared food for baby in the kitchen. The cook thought it was so sad that Aunt Do was going to such a faraway country, and that by proxy.

Once the van Nagells gave a dinner for the Queen of Romania (the King did not come, he was always drunk). Once, too, the Crown Prince and Crown Princess came to lunch.

Anyone who thinks that high-level cultural matters were discussed over dinner is wrong. It was usually about three things: the food, the servants and étiquette. Especially étiquette was the topic of conversation, for instance how many buttons there should be in the folds of the second servant’s livery .

The baron was a witty man. He had met and married his wife in America. He told Aunt Do, when she looked at the wedding photos, that during the wedding ceremony he wore the costume of the Johanniter Order, a red cloak with a white cross. The next day, the US newspapers reported that the bride wore a fox hunting costume. He liked that, but Mrs van Nagell found it less funny.

Jeanette had very few clothes. In winter, she was dressed warmly because the snow was one metre thick. She had only one pair of woollen trousers, whose crotch was completely patched. When the woollen trousers were in the wash, there was no walking. Then a servant appeared with the message: “People had inquired why the young baroness did not go out today”. “Yes, unfortunately she couldn’t because her woollen trousers were in the wash”. The little boy had a jumper that was completely felted and difficult to put on and take off. Auntie Do and Fraulein had to take the jumper off him together, it was that awkward. But, when he had to have real boy clothes, Bucharest’s first tailor was called for. When Jeanette went to a ball masque, she did wear a beautiful rococo costume with a big wig (she stood out from all the Little Red Riding Hood and Hansel and Gretel at the ball) .

Aunt Do returned to Holland at the end of June 1925, staying at “De Schaffelaar”, where she was praised to the skies for 14 days. The child behaved exemplarily: she no longer ran around the table, had made crafts for the whole family and could even read from the Bible, which brought tears to the grandparents’ eyes. “How sad we are that you are getting married,” they told Aunty Do. “No one has lasted as long with “her” as you have”. She got a beautiful certificate, and later she also got letters from Mr van Nagell, but it was not a job to do for more than a year. Aunt Do had met hardly anyone her own age all this time and had been relatively alone.

Aunt Do did find that she had learned a lot, such as how to set tables and serve on all kinds of occasions, how to write official letters, etc. etc. She also learned that no matter how high someone was, there was always someone else who was even higher.